Wikiji: EDA

How frequent are various Kanji on Wikipedia?

Introduction

Where does a Japanese learner begin when facing the daunting challenge of learning thousands of kanji? This is the question that motivated me to do this project and the one I hope to help answer in this blog post. Hopefully by looking at my compiled data concerning kanji frequencies from Wikipedia in conjunction with other sources, the answer to this question will be slightly clearer.

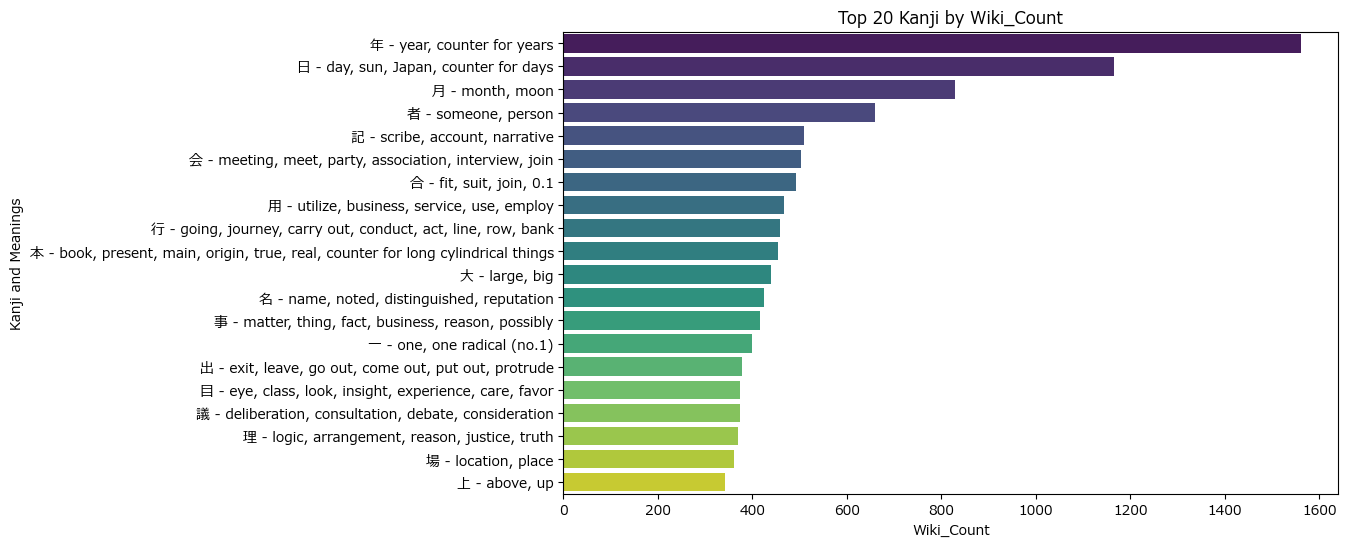

What are the Most Common Kanji on Wikipedia?

The top 3 most common kanji are 年、月、and 日. If you were considering using Wikipedia as a source of reading practice in Japanese, expect to be reading a whole lot of dates. Curiously, we also see that kanjis 4-8 are all non-N5 level, which is an indicator that the JLPT may not be the definitive ranking for usefulness of kanji, which will be explored more in final section of this post.

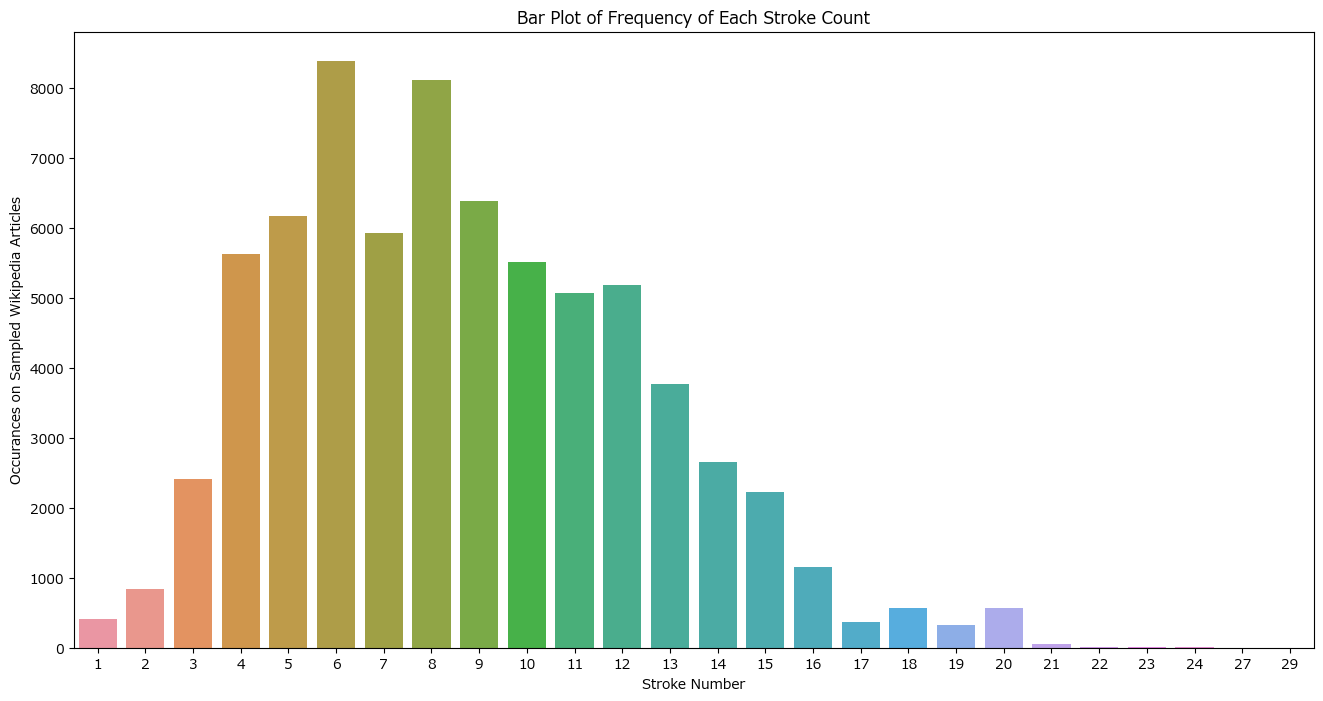

Now we will briefly look at how complex the kanji that are appearing on Wikipedia are. To be clear throughout this post unless otherwise noted, when I say complexity I mean how complicated they are to write not necessarily how complicated the ideas they represent are.

We see from here that the most common number of strokes for kanji is in the 4-10 range. However, there is still a tangible amount of frequency going all the way up to 21.

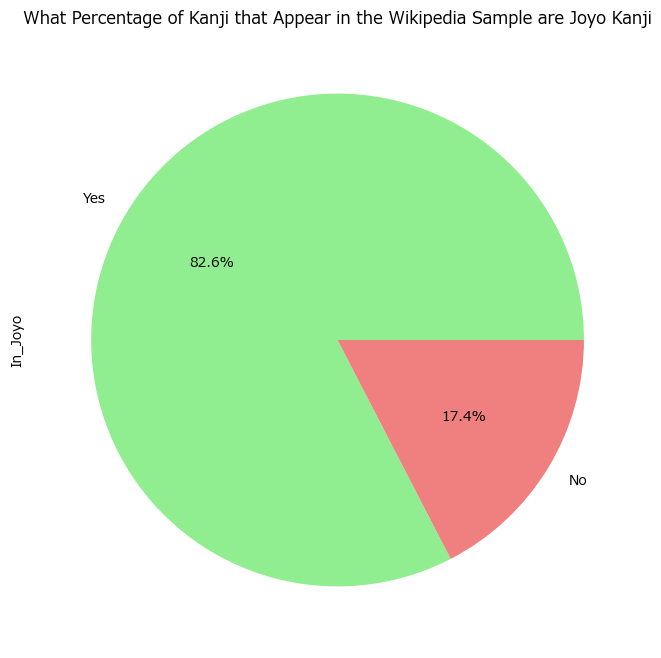

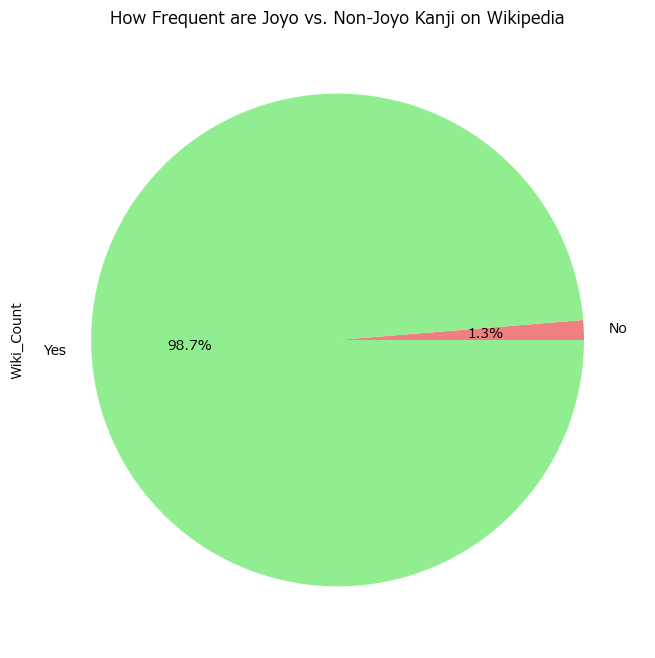

As described in the previous blog post, the Joyo list is the list of 2,136 kanji deemed by the Japanese government to be necessary to be considered fluent in Japanese. The question is how common are non-Joyo kanji and which characters beyond this list are the most essential for learners.

Here we see that while 17.4% of unique kanjis from my DataFrame are non-Joyo, the frequency with which they appear on Wikipedia is only 1.3%. This means that while there are a fairly large amount of non_Joyo kanji that appear, most of them do not show up with much consistency. The five most common non-Joyo kanji from my sampled Wikipedia pages are:

- 蘭 (orchid, Holland) - rank 550

- 智 (wisdom, intellect, reason) - rank 783

- 之 (of, this) - rank 785

- 幌 (canopy, awning, hood, curtain) - rank 814

- 乃 (from, possessive particle, whereupon, accordingly) - rank 825

Any intermediate Japanese learners looking at this post should consider adding these kanji to their study list/flashcard deck.

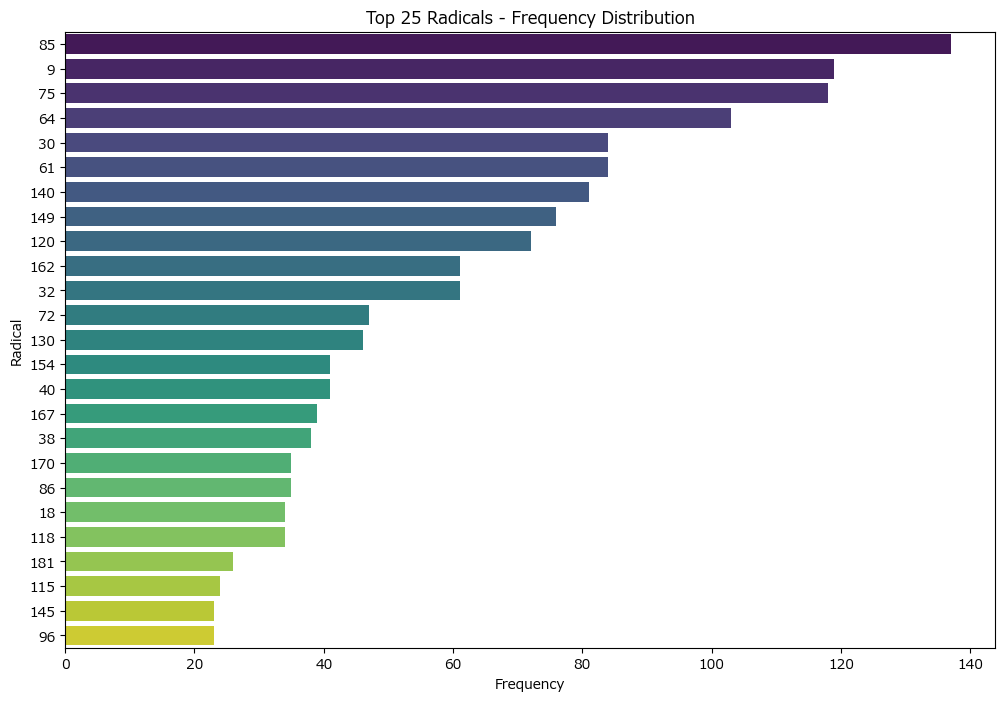

The final thing in this section is we’ll be looking at which radicals appear in the most kanji. Radicals are the building blocks of Kanji. For example the kanji 間 is composed of the radicals 門 and 日。Due to the complexity of printing radicals (radicals can have different forms and positions) I will be using the number codes for the radicals. Breaking down these numbers would be a bit too complex for this blog post, but more information can be found here.

How do Frequencies Differ Across Sources?

Of course the question of frequency of kanji is not a new one, but I think the approach to defining frequency is often flawed. Most dictionaries (such as the very popular jisho.org) will define the frequency of kanji based on how often they appear in Japanese newspapers. This isn’t necessarily a bad way to define frequency, but for learners it can also be misleading as to how essential some kanji are. For example the kanji 閣 is rated as the 444th most common kanji in newspapers. This would indicate that its frequency is around what a late beginner/early intermediate learner should be looking at. This kanji, however, has essentially only one word it is used in which means cabinet as in the presidential cabinet. While this word is certainly worth knowing, I don’t think anyone would argue this character should be a higher priority for learners than 母 (mother) which is ranked as the 570th kanji in newspapers.

Other less common methods of ranking kanji frequency also exist such as frequency in manga or frequency in novels, but these methods have similar issues with niche language being overrated. Looking at Wikipedia instead of newspapers or manga does not eliminate the overrating of niche kanji, but by seeing a ranking of frequency in multiple types of sources side by side learners get a more complete view of what is essential and what can be saved for later.

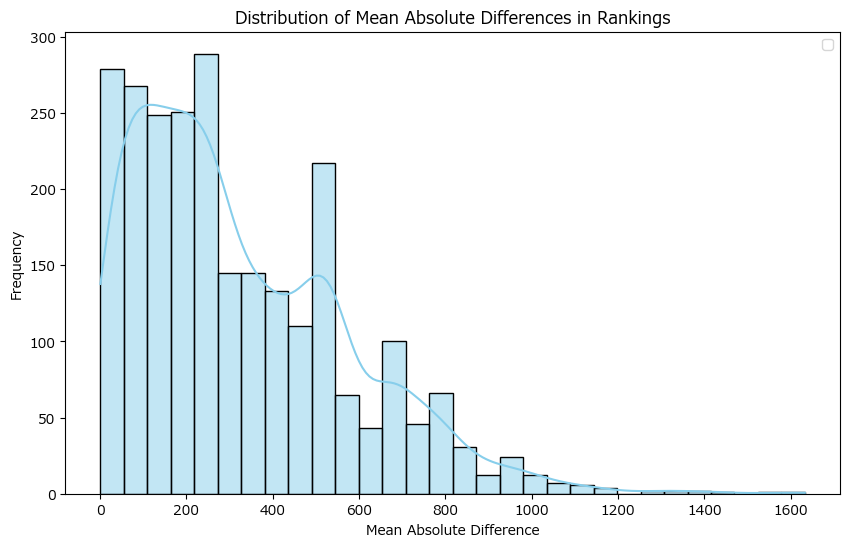

From this plot we can see that as expected there are a lot of kanji that are similar in frequency across different types of sources. It comes as no surprise that “行” (go) is extremely common across all types of sources and “唄” (song praising Buddha) is infrequently used in newspapers, novels, and Wikipedia. The most interesting thing to look at here is what are the kanji that have the widest difference in usage across different sources. The five kanji with the highest mean difference between sources are:

- 票 (ballot, label, ticket, sign)

- 該 (above-stated, the said, that specific)

- 訂 (revise, correct, decide)

- 項 (paragraph, nape of neck, clause, item, term (expression))

- 栽 (plantation, planting)

It is easy to imagine why these five characters maybe more common in newspapers specifically than in other sources.

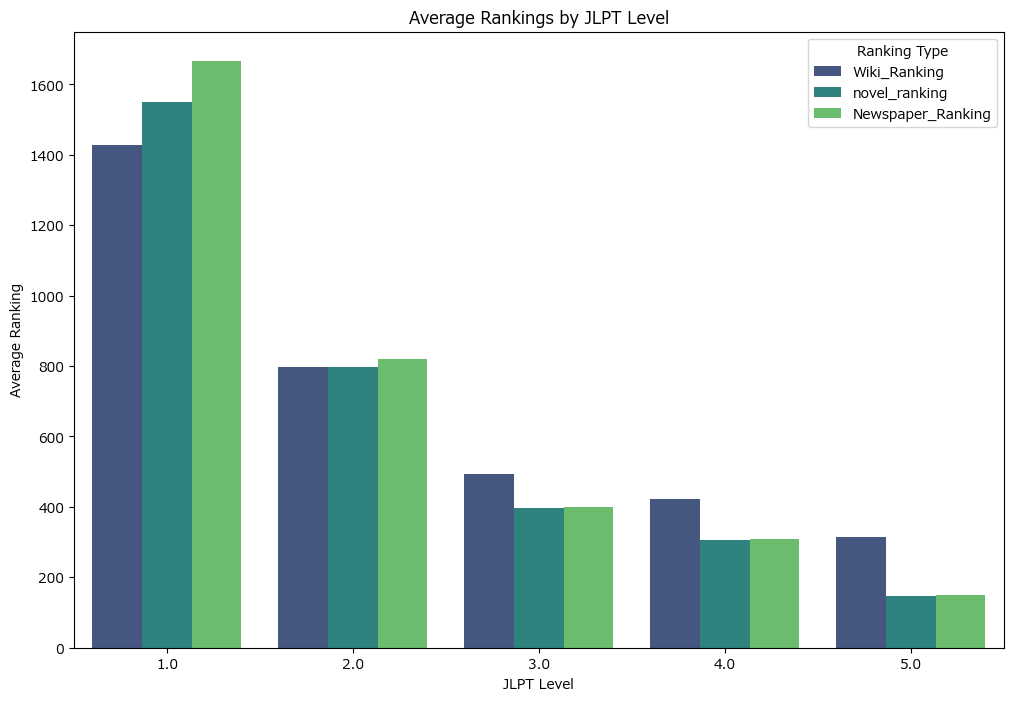

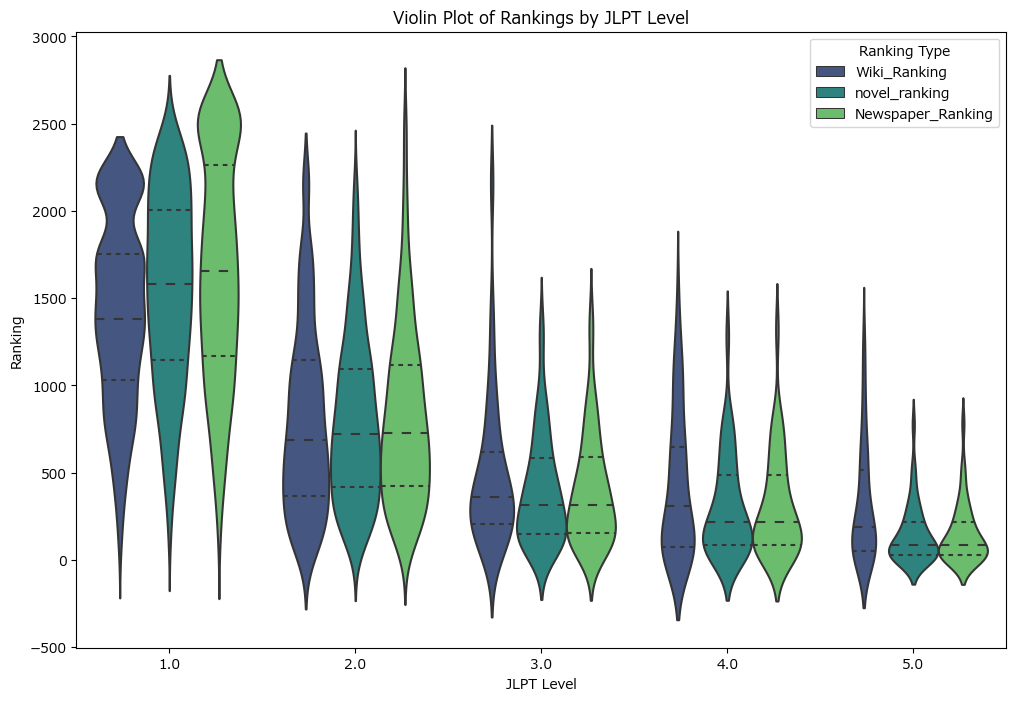

This plot shows us that newspapers tend to use the most advanced language and Wikipedia uses the most elementary.

Looking at the JLPT

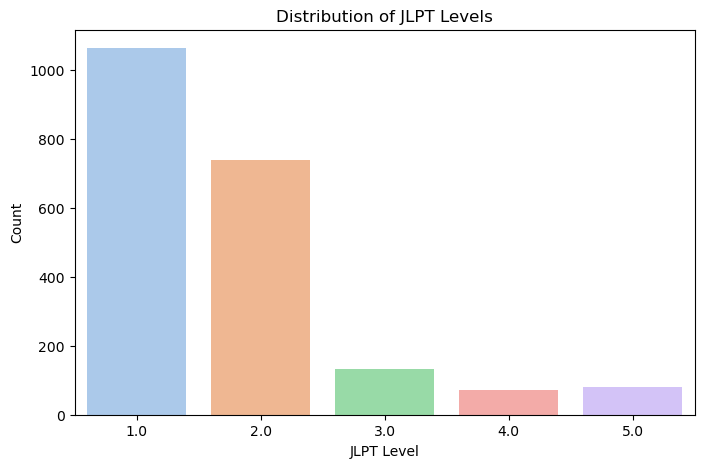

The JLPT is a common resource that students use to guide their progression through learning vocabulary, grammar, and of course kanji as well. It is important to note that no official list exists of what kanji goes with which level of the JLPT and so assignment of level is based purely on historic trend. As is well known, the JLPT does not evenly distribute kanji across all levels. As we can see below, the N1 and N2 levels require a dramatic increase in kanji knowledge.

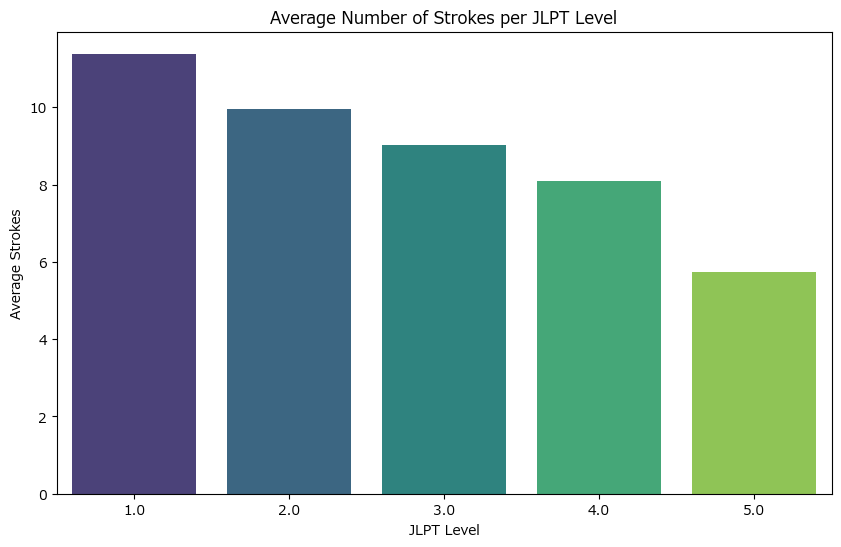

We also see that, pleasantly, the more advanced JLPT levels feature kanji of higher complexity. This goes against what I’d have thought as higher level kanji are generally considered higher level due to the complexity of ideas or rarity and not written complexity, but it appears that written complexity may also be a factor in determining the level at which kanji are taught.

The following plot shows the truth behind my previous hypothesis that JLPT levels for kanji are also connected to how common they are. However JLPT level and rarity are not perfectly correlated. We can see from this plot that while N5 kanji do tend to be more common, there are kanji whose frequency would indicate they should be at a beginner level at the N1 and N2 levels.

Conclusion

I hope that for any Japanese learners reading this post that looking at the frequency of kanji in what may be a new way helps clarify some things. I hope for those not interested in Japanese that you were still able to get something out of this post. I’d also like to encourage everyone to learn languages whether Japanese or otherwise. Language learning is fun and its one of the best ways to expand your worldview.

If you would like to see the code used to make this post or make a deeper dive into my project you can find my GitHub repository here.

Basic Glossary of Terms

- Kanji: One of the three sets of written characters used in Japanese. Originated in China.

- Radical: The building blocks used to make kanji.

- JLPT: Japanese Language Proficiency Test. A series of five exams used to measure Japanese fluency. N5 is the lowest level and N1 is the highest. Common barometer used by foreign learners to determine order to learn things.

- Joyo: The list of 2,136 kanji taught to Japanese students created by the Japanese Ministry of Education.